What Was The Rush?

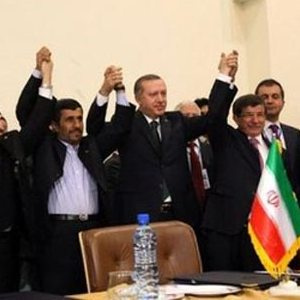

11 PM on May 16, 2010, could be considered a turning point in Iran’s nuclear diplomacy –and indeed the whole nuclear saga. After months of intensive diplomacy carried out by Iranian diplomats, news agencies reported that Turkish Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdogan had cancelled his official trip to Azerbaijan in order to instead pay a visit to Tehran. Headlines the next day proclaimed the big news: Tehran had given the nod to a nuclear fuel swap deal, and Turkey would host its uranium stockpile. The Tehran Agreement seemed to satisfy the demands of the global powers –or at least it appeared so for a few hours.

For a few hours –that’s right, just a few- it seemed that the course of Iranian nuclear developments was headed to a big shift. The cautiously supportive stance of international officials and Western countries overshadowed the few negative remarks. All-out endorsement of the agreement inside Iran -and working out such a deal in itself- attested to Iran’s determination to follow the diplomatic path.

Hillary Clinton’s remarks –that the draft sanctions resolution was ready to be put to a vote in the UN Security Council- came as the bigger surprise, however. And as if that shock was not strong enough, Russian officials expressed lukewarm support for the Tehran Agreement and the Chinese took an ambiguous stance. Reactions from France and Britain were predictable -though London did not come across as tough as one might expect from a Tory government.

Nevertheless, China and Russia were perhaps more willing for the sanctions resolution to be delayed right when the ink had barely dried on the Tehran Agreement. Lavrov’s remarks on a June 4 visit to Beijing were a sign: “We are against forcing the voting process,” he said then. Despite that, the next day, President Dmitri Medvedev showed a different reaction after his meeting with Germany’s Angela Merkle: “Nobody wants sanctions, but in some cases there is a need to agree on them,” he was quoted as saying. Undoubtedly, sweeteners by West had been tempting enough to convince China and Russia to shift their positions. Washington’s confident tone was evidence that it had bought the consent of Moscow and Beijing.

Pushing for a new round of sanctions just a few hours after the Tehran Declaration raised eyebrows and triggered a wave of analysis over Washington’s motives. Tehran’s dubious intentions, the West’s diplomatic mistakes, and the global power’s irritation at rising powers Turkey and Brazil, were key phrases in these assessments of the situation. Nevertheless, they all failed to answer the one important question: why didn’t Washington wait for at least another week before submitting the draft resolution?

Unlike its Viennese precedent, the Tehran Agreement was detailed, clear-cut and scheduled. Based on the agreement, Iran would officially notify the IAEA within one week and work out a practical procedure to implement it with the Vienna Group (France, Russia and the United States). But Washington did not even wait for the IAEA’s response to Iran. As it happened, the UN nuclear watchdog replied to Iran’s official letter a few hours before the fourth round of sanctions were passed.

The irony is that signatories to the Tehran Declaration, namely Turkey and Brazil, both enjoy close relations with the United States and both have publicized their correspondences with Washington over the nuclear negotiations in Tehran. The letters exchanged between Obama and Lula, and Obama and Erdogan, bear witness to Washington’s schizophrenic behavior. Interestingly, rumors are that Erdogan attended the negotiations after talks with U.S. Secretary of State Hillary Clinton over the phone.

Even if Iran was trying to waste time, the West could have certainly waited a few weeks, if only as a sign of appreciation of the efforts made by middle-ranked powers Brazil and Turkey, and to avoid stirring a negative reaction in global public opinion. A hypothetical failure of consequent negotiations between Iran and the Vienna Group would ease the problems of China and Russia in justifying their shifting stance, and Moscow would not have had to engage in the current row with Iran. The West could also have spent less capital in appeasing these two countries. At any rate, Russia could have avoided the haste in approving a new sanctions resolution.

Not only could the complementary negotiations have raised the statuses of Ankara and Brasilia, but also they could also have helped the Ahmadinejad administration disarm the opposition. Depriving the Iranian president from this opportunity might partially explain the haste of the global powers in slamming the door shut on the Tehran Declaration.