After the Nuclear Deal, Iran Turns Towards Caspian to Restore Rights

The Special Working Group to Draft the Convention on Legal Status of the Caspian Sea held its 47th session in Tehran on October 23rd. The two-day meeting ended yesterday.

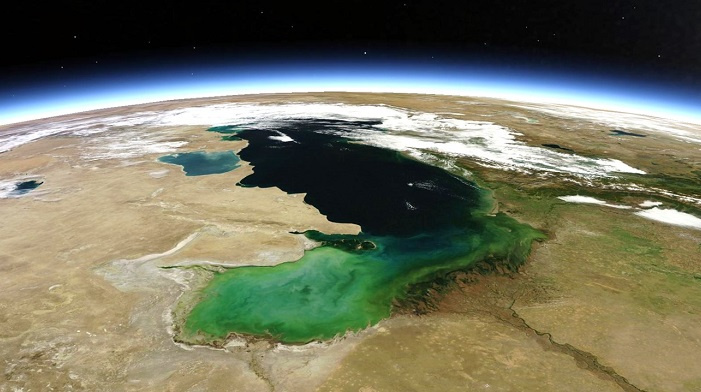

Iran’s Foreign Minister Mohammad-Javad Zarif was the keynote speaker of the convention. Zarif was diplomatic and complimentary in his speech, praising the “friendly, constructive atmosphere” of the special working group meetings, and the “tangible progress” made on drafting the convention on legal status of the world’s largest lake. He did, however, make veiled reference to points of contention between Caspian littoral states, or to better put it, Iran versus the four other countries bordering the lake, namely, Russia, Kazakhstan, Turkmenistan, and the Republic of Azerbaijan. Fair demarcation of maritime territories, navigation exclusively under flags of littoral states, demarcation of basin and sub-basin borders for exploitation of resources with consideration of geographical features of every littoral state were some of the points briefly addressed by Zarif.

The Caspian Sea used to be Iran’s main diplomatic concern during the late 1990s and well into the 2000s, before the nuclear standoff between Tehran and the West took off and overshadowed nearly every other diplomatic concern of the country. Two treaties of 1921 and 1940 between Iran and its sole Caspian neighbor, the Soviet Union, had provided a convenient framework for both countries in navigating the sea and sharing its resources. But those treaties belong to an era long gone: the early years of the Soviet rule, and from a relatively equal footing for both sides, rendering them fair and sustainable.

With breakup of the soviet communist republic, Iran had to face four new neighbors, each scrambling for its share of the Caspian Sea, and its rich fisheries and energy resources. Since the first meetings over the legal status of the Caspian Sea, in terms of delineation of maritime borders, division of basin and sub-basin resources, and navigation rights, Iran has stuck to the two Soviet era treaties, stating, at times to soothe domestic nationalistic concerns, that it recognizes these two historical documents as the only basis for any further agreement.

The demarcation of maritime borders and division of the surface of the sea was a particularly sensitive issue for Iran, with claims of its share from Caspian surface ranging from 50% (Iran’s supposed share in the Soviet time) to 20% (equal shares for every littoral state). Yet, the formula backed by other Caspian states allocated Iran a mere 13 percent sounded humiliating and against historical rights inside the country.

Despite Iran’s objections, Russia led a series of bilateral and trilateral talks with other states bordering the sea to delineate maritime borders. Iran’s entanglement with the nuclear program left little maneuvering space for it to place pressure on either Russia, its lukewarm supporter in the nuclear struggle, or any other state for that purpose.

In an interview with the Reformist Omid-e Iranian daily, Elaheh Koulaei, former Reformist MP and an Caspian affairs analyst provides a detailed picture of the situation:

“Iran was sidelined in the negotiations by other littoral states” says Koulaei. “They have done their utmost to meet their own interests and transfer energy exploited from the sea [resources] to the international market. International data show that all littoral states have used Caspian basin’s resources except Iran” she adds. “We have only objected and released communiques.”

Koulaei attributes failure of Iran’s Caspian diplomacy to “unrealistic, inappropriate diplomacy”, but expresses conditional optimism that the post-JCPOA atmosphere has given Iran the opportunity to bargain from a reinforced, more balanced position against other littoral states and achieve a comprehensive agreement, a “legal regime”, for the Caspian Sea.

“After successful nuclear negotiations and implementation of the JCPOA, which has elevated Iran’s international status, Iran can rely on the diplomatic power gained from the nuclear deal and its exceptional geostrategic position … to regain its interests, in case it takes advantage of its diplomatic leverage correctly” she says.