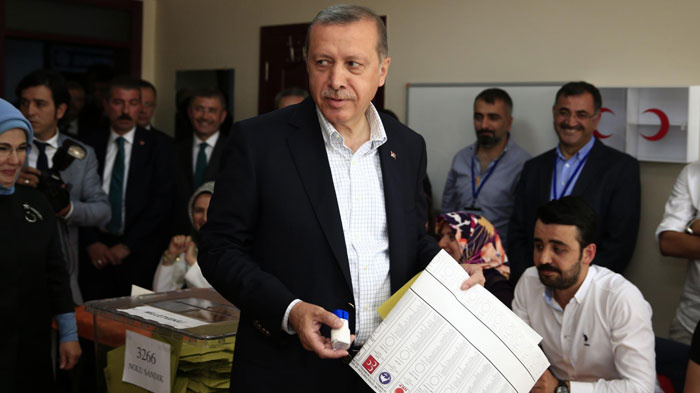

Erdogan’s party loses majority as pro-Kurdish HDP gains seats

Turkey’s president, Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, has suffered his biggest setback in 13 years of amassing power as voters denied his ruling party a parliamentary majority for the first time since 2002 and gave the country’s large Kurdish minority its biggest voice ever in national politics.

The election result on Sunday, with almost all votes counted, appeared to wreck Erdoğan’s ambition of rewriting the constitution to establish himself as an all-powerful executive president. Erdoğan’s governing Justice and Development party, or AKP, won the election comfortably for the fourth time in a row, with around 41% of the vote, but that represented a steep fall in support from 49% in 2011, throwing the government of the country into great uncertainty.

The vote was the first time in four general elections that support for Erdoğan decreased. The fall coupled with an election triumph for a new pro-Kurdish party meant it was unlikely that the AKP would be able to form a majority government, forcing it to negotiate a coalition, probably with extreme nationalists, or to call a fresh election if no parliamentary majority can be secured within six weeks.

The new party, the HDP or Peoples’ Democratic party, largely representing the Kurds but also encompassing leftwing liberals, surpassed the steep 10% threshold for entering parliament to take more than 12% of the vote and around 80 seats in the 550-strong chamber.

The HDP victory denied Erdoğan’s party its majority. Erdoğan campaigned to secure a minimum of 330 seats in the parliament, a three-fifths majority that would have enabled him to call a referendum on the constitution with a view to converting Turkey into a presidential rather than a parliamentary system. But the AKP appeared unlikely to muster even a simple 276-seat majority.

“We expect a minority government and an early election,” a senior AKP official told Reuters.

The prime minister and nominal head of the AK party, Ahmet Davutoglu, had promised to resign if he failed to obtain a simple parliamentary majority. With internal dissent rumbling in recent weeks within the government ranks and at the top of the AKP, the poor result for Erdoğan is likely to embolden dissenters and could spark a power stuggle.

The atmosphere outside the AKP’s headquarters in Ankara was muted. Several hundred supporters chanted for Erdoğan, the party’s founder, but there was little sign of the huge crowds that gathered after past election victories.

In the conservative district of Tophane, an AKP stronghold in Istanbul, only a couple of men were sitting in a local teahouse to follow Davutoglu’s balcony speech.

“I am not unhappy,”, said Nusret Aksoy, 50. “The AKP came out the strongest party by far.” Pointing at the TV screen, he added: “Look, do these crowds seem unhappy to you? They are not. These elections were good and democratic.”

He added that he was satisfied that the HDP managed to get into parliament: “The people gave them a chance to prove themselves. Now they have to show everyone what they are really made of, that they are not just talking, but also capable of delivering.”

By contrast, thousands of jubilant Kurds flooded the streets of the south-eastern city of Diyarbakir as the results came in. Erdoğan had repeatedly lashed out at the HDP and its charismatic leader, Selahattin Demirtaş, before the election. Demirtaş promptly ruled out a coalition with the AKP.

“This result shows that this country has had enough. Enough of Erdoğan and his anger,” said Seyran Demir, a 47-year-old housewife who was among the thousands who gathered in the streets around the HDP’s provincial headquarters. “I am so full of joy that I can’t speak properly.”

In Istanbul, enthused crowds chanted “we are the HDP, we will be in parliment” outside the press conference Demirtaş held in Istanbul on Sunday night.

“I am so happy,” said Bülent Aras, 40. “This means that there will be peace, the war is over. This party represents everyone. We will finally all be equal in Turkey. This will put an end to the corruption.” He added that he was not surprised about the results. “We expected to do well. It was time for change.”

“I had hoped for this to happen,” said 61-year-old painter Mehmet Hakki Sabancali. “I was so nervous that the HDP might not get 10%. This rings in a new Turkey. The HDP will do away with old taboos: with LBGT rights, gay marriage, conscientious objection and non-Muslim minorities.”

As head of state since last August following a triple term as prime minister, Erdoğan was not on the ballot. But the election was, in effect, a referendum on whether to give his office extraordinary powers that would significantly change Turkish democracy and prolong his reign as the country’s most powerful politician.

Voters roundly rejected that ambition, with the Kurdish vote in particular swinging the election against the incumbents on an unprecedented scale. The 10% hurdle, dating from the military-authored constitution of 1980, had been intended in part to diminish Kurdish representation in the parliament.

The HDP gambled on breaking the built-in disadvantage and triumphed. If it had fallen short of 10%, it would have forfeited all seats.

Erdoğan’s divide-and-rule strategy of rallying his religious-conservative base has led to increasing polarisation in Turkey, and in some cases to violence.

In the runup to the election, the HDP reported more than 70 attacks on election offices and campaigners across the country. On Friday, two bombs exploded at an election rally in Diyarbakir, killing three and wounding hundreds of others.

Official results based on 99.9% of votes counted gave the AKP 41%, followed by the Republican People’s party (CHP) on 25%, the Nationalist Movement Party (MHP) on 16.5% and the HDP in fourth place with 13%.

Turnout was at 86%.

“This is the end of identity politics in Turkey,” said Gencer Özcan, professor for international relations at Bilgi University in Istanbul. “The election threshold is not the only barrier that was overcome tonight in the elections, but also emotional and identity barriers have been breached. This is a golden opportunity for the HDP. Voters in Turkey endorse democracy in Turkey across identity boundaries.”

The HDP ran on a platform defending the rights of ethnic minorities, women, and lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender people. In a polling station in the predominantly Kurdish suburb of Dolapdere in Istanbul, Hacer Dinler, 25, said that she had high hopes for the HDP.

“If they make it into parliament, everything will be better,” she said. “We will have more MPs to speak for us, which in turn will strengthen the peace process.”

The HDP success marked a sea-change likely to have a big impact on national politics. Shackled by the high threshold, pro-Kurdish candidates had previously run as independents in single seats to try to beat the 10% party barrier. But the HDP also successfully sought to reach beyond Turkey’s roughly 20% Kurdish population, attempting to woo centre-left and secular voters disillusioned with Erdoğan.

“The reason the HDP has won this many votes is because it has not excluded any members of this country, unlike our current rulers,” said 25-year-old Siar Senci. “It has embraced all languages, all ethnicities and members of all faiths and promised them freedom.”

The secularist Republican People’s party will be the second biggest group in parliament. Murat Karayalçin, the party’s Istanbul chairman, said the outcome was a “clear no” to the executive presidential system championed by Erdoğan.

The rightwing MHP, long seen as the AKP’s most likely partner if it tried to form a coalition government, took close to 17% of the vote. The deputy chairman, Oktay Vural, said on Sunday it was too early for him to say whether it would consider forming a coalition government with the AKP. “It would be wrong for me to make an assessment about a coalition, our party will assess that in the coming period. I think the AK party will be making its own new evaluations after this outcome,” Vural said.

The high stakes of this year’s parliamentary elections mobilised a large majority of the population to vote. Aliye Goga, 39, a woman of Armenian descent, said it was the first time she had voted. “I just never saw the point before,” she explained. “Now my eyes have opened up. The HDP is the only party for women in this country, and they make realistic promises.”

Leyla Çelik, 38, a part-time student voting in Istanbul’s conservative Fatih district, hoped the AKP would continue in power. “This government has exceeded all my expectations. We have good healthcare, and women can go to school and university with a headscarf. They are a party that treats us like human beings.”

The Guardian