The 2008 American Recession: The Drama, Lessons Learnt

By Ali Kharazi

Most economists have now moved away from debating the likelihood of a recession in America and are now discussing the depth of the coming recession. In this light, some economists have argued that the 2008 recession will be more protracted and painful than the short recessions of the 1990-1991 and 2001, as unlike 2001 when only technology investments had been hurt, most components of aggregate demand are now under threat. As of Friday, the risk of a recession in 2008 was publicly acknowledged by the Bush White House and the US government is now scrambling to boost the economy and prevent it from a further slide. What events have led to the 2008 American recession and how are international markets and governments reacting in response? What lessons can we learn of this financial drama thus far?

Before we delve deeper into the subject matter, it is essential to see how a recession is defined. In macroeconomics a recession is a decline in a nation’s GDP for two or more successive quarters of years. In the US, a recession is ambiguously defined by the National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) as ‘a significant decline in economic activity spread across the economy, lasting more than a few months’. This negative real economic growth can be associated with falling prices (deflation) or rising inflation (stagflation). Although the distinction between a depression and a recession is less clear it can be said that a protracted and severe recession is known as an economic depression. To put all this into perspective, while most economic slowdowns, such as in 1973, 1979, and 2001, are described as recessions, the American economy experienced a depression in the early 1930’s and so did the ‘Asian miracle economies’ in 1997.

The causes of recessions are fiercely debated among economists and at best can be viewed as a puzzle consisting of a combination of endogenous business cyclical forces and exogenous shocks. Top of the list in this puzzle is the crisis hit US building industry, 15% of the US economy, where it not only faces a crash in property prices but also critical problems in its subprime mortgages –estimated at $100 billion worth of mortgage defaults. Although, these figures are small in relation to America’s $13.2 trillion GDP, the relevant importance of the US building industry has leveraged this sector specific crisis into damaging the financial industry and the economy as a whole. In the past five years, the private sector has increased its role in the mortgage bond market which is valued now at $6 trillion, the largest part of the whole $27 trillion US bond market. The increasing proportion of banks’ portfolios holding mortgage backed securities led to heavy losses of up to $60 billion worldwide as a result of the recent defaults. Large bondholders, such as pension funds and hedge funds whom bought subprime mortgage bonds have also been hurt with the value of these bonds being valued between 20% and 40% of their original value. Overall, it has been estimated the financial institutions may have suffered losses up $500 billion dollars as a result of the revaluation of the subprime mortgage bonds.

Other factors adding to the likelihood of a recession is the weak dollar, the high price of oil which is trading between $90 to a $100 a barrel, and a sluggish job creation. All these events have added to an environment of uncertainty and have forced financial lenders to cut back on the amount of credit available on the market and in effect slow down economic activity. On December 18th five central banks, the European Central Bank, Bank of England, the Fed, and the national banks of Canada and Switzerland, in reaction to the credit crunch made available $110 billion in auctions to the world money markets and lowered their respective national interest rates to ease lending and avoid a global crisis. However it seems that although this unprecedented international coordination of monetary injection helped ease the shortage of cash in money markets, it has done little to bring back confidence to investors. This has been clearly evident in stock markets across the world have with Londons FTSE losing 5% of its value in the last week and Wall Street and other Asian markets showing increasingly volatile trading.

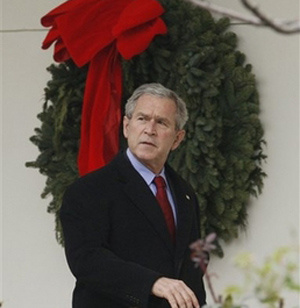

Feeling the political heat to intervene in the markets, the Bush White House on Friday announced a stimulus package worth $145 billion dollar as a ‘shot in the arm’ for the ailing US economy. US officials are also talking of sending rebate checks up to $800 for individuals and $1600 for households. Bush however didn’t give out the operational details of the stimulus plan and did not say how the government intends on paying for the package. The plan which needs to be approved by congress first, was not well received by markets and stock indices continued to fall after the president completed his speech on Friday. Investors are already feeling wary of rising governmental costs and increasing national debt, with the Iraq war estimated to cost up to $2 trillion dollars by Nobel prize winner Joseph Stiglitz or $10 billion a month by other estimates, few still maintain strong confidence in Bush’s economic management. "The fear is that the plan, and even the Federal Reserve, may not have enough firepower to turn the path to recession around," said Richard Sparks, senior equities analyst at Schaeffer’s Investment Research in Cincinnati.

Little can be said with certainty of what will happen to the US and the world economy in the next few months. However, many significant lessons can be learnt from this financial drama thus far:

1) The increasing integration of international financial intermediaries makes a financial crisis reverberate globally as was the case with the US subprime mortgage crisis. As the renowned prophet of markets, Alan Greenspan, stated recently: ‘We concluded that the monetary forces that were arising in the world globally had become so overwhelming, relative to the resources of central banks that we had effectively lost control of long-term interest rates”. In this light, crises affecting markets internationally require more coordinated action between central banks; the $110 billion monetary injection by 5 central banks in the recent crises should be made more common in dealing with future crises. Furthermore, international bodies such as the UN and the World Bank should take more active roles in future global crises and especially protect countries with developing economies from powerful financial shocks.

2) The American mismanagement in the financial industry has cost the word dearly and is a further blow to its prestige as the leading economy of the world. Investors are choosing American markets less in recent years due to stringent financial auditing laws and a post-911 political and security paranoid environment. The decline of the American economic prestige is best seen with London replacing New York as the undisputed financial capital of the world. Weather this fall in prestige prompts the US government to shift towards a more open and multilateral economic policy, especially in relation with developing countries, is to be seen.

3) Returning confidence to an economy is not easily accomplished solely through governmental financial intervention and needs to be complemented with a program aimed at the behavioral aspects of mass economic decision making. Humans are rationally bounded and therefore the psychological and behavioral aspects of economics especially at times of the crises needs to be studied more in depth.